Bedrock to Birds: Plants, Animals, And Human History

By Chris Ajello and Alicia Daniel

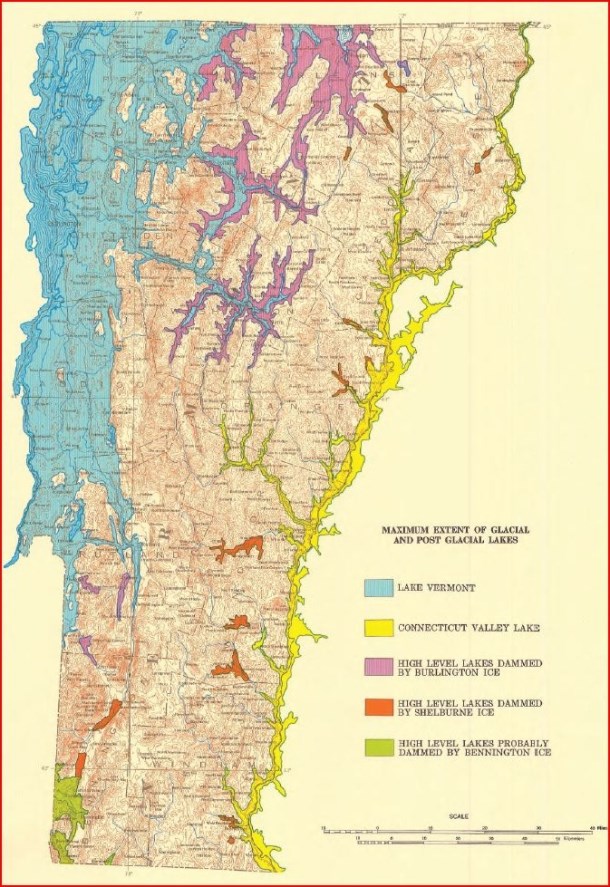

This is the second part of an article exploring the incredible diversity of Burlington’s landscape across space and time; in particular, we will carry the connections from part one—from oceans, to continental upheaval, to glaciers—forward into the living landscapes of today. For example, how do the seemingly bottomless deltaic sands at Starr Farm continue to influence plant communities so long after the Winooski has changed its course? How does the calcium rich bedrock, formed by the accumulation of shells on ancient ocean floors, write itself in the carpet of ephemerals throughout our spring forests at Rock Point and Arms Forest? Put otherwise: how do these relics of a distant world constrain and shape what we see today?

Translation by plants

Plants, by presence or absence alone, can unveil features of a landscape otherwise hidden. And when they band together in communities, these hidden features become even easier to pick out. In Burlington, the dolostone bedrock topping the Champlain Thrust fault has written itself into the limestone outcrop communities found from Kingsland Bay, and Red Rocks to Lone Rock Point, Niquette Bay and beyond. These communities occupy the narrow bands of ledges along the lake–or not far from it—and are best recognized by the gnarled, bonsai-like aspect of white cedar. This tree is masterful at anchoring itself to exposed rock—and thrives on the rich deposits of marine calcium that are slowly released from the dolostone. In fact, a panoply of calcium-loving shrubs have also found their way here among the cedars: New Jersey tea, leatherwood, orchids, and several native honeysuckles, as well as the unique species of sedge and fern that spring right from the rock face. Just beyond these ledges, where the soils are deeper and shelter from the lake is greater, hardwood communities form a totally different world, where sugar maple, basswood, and white ash tower overhead.

Moving inland from the lake, one arrives in the vast floodplain forests that define Burlington’s lowland landscape; these are best found in places like the Intervale, Derway Island, and Macrae Farm. Massive cottonwoods and silver maples arch across prehistoric mazes of ostrich and cinnamon ferns. Here, the nutrient rich clays and silts deposited yearly by storms and the spring thaw connect these communities less to the bedrock than to the Winooski River, itself more ancient than the glaciers, the lake, and possibly the Green Mountains, which it deftly crosses through.

The Burlington uplands, however, are marked by deep sands, too porous to hold much water or nutrients. Remember, these sands are remnants of the ancient delta where the Winooski once emptied to the Champlain Sea. Sunny Hollow and Starr Farm Park are great examples of what might once have been the dominant community before the city was built: pines and oaks in the canopy, with hardy shrubs, like blueberry, in the understory. In fact, these woods are dry enough to be shaped by fire: burn scars are found here and there at the base of trees, while fire adapted species–notably the pitch pine–thrive here, as nowhere else in the region.

But perhaps the most unique community of plants in the Burlington region is found in the rare but persistent sand dunes along the lake shore. Their shifting slopes are dotted with species of grass and legumes common along the Atlantic coast; and indeed, these communities are vestiges of the time of the Champlain Sea nearly 9,000 years ago, when the whole Champlain basin was merely an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean.

Translation by wildlife

Unlike its plants, Burlington’s wildlife cannot be so directly linked to bedrock and ancient oceans; the basic drives for food, shelter, and mating renders the Burlington landscape in a remarkably different light. Nonetheless, wildlife can be acute readers of landscapes, and by their signs alone, one can see how the niches and habitats here are nonetheless connected to events of the distant past.

Over millennia, for example, Burlington’s deltaic sands and floodplain silts have proved especially vulnerable to erosion, and today they’re deeply incised by small waterways, like Centennial and Potash Brooks. These wind their way to the Winooski River or to Lake Champlain, creating extensive networks throughout the city, connecting the uplands and points east to these large bodies of water. In many such areas, construction and cultivation has been naturally delimited. This in turn has opened the door to many specialists, like river otters, muskrats, mink, and beavers, signs of which are abundant along the shores and banks throughout Burlington. But this landscape also provides habitat, cover, and browse for other less specialized species, like deer, raccoon, and red foxes, who are deft at exploiting the fruits of a fractured urban environment.

Development and cultivation have likewise been delimited by the dolostone ledges and outcrops described above. Today these areas, chiefly along the Champlain Thrust Fault, constitute some of the most expansive forests in Burlington. This fact is not lost on what are normally deep-woods species, like the Barred Owl and Hermit Thrush, who have made these parts of Burlington home.

Humans: a transformation

The presence of humans in Vermont is traceable only to the end of the last ice age, as the glaciers left no earlier evidence in their wake. Before contact with Europeans, some estimates of native populations in Vermont are around 10,000 people, but the intensive management regimes recorded elsewhere—such as fire to control the underbrush or large-scale land clearing for firewood and agriculture—were likely absent from the Burlington area. Instead, the region’s expansive waterways were used for transportation to and from the otherwise inaccessible mountain wilderness, rich with fish and game. In fact, spearheads found in the Burlington area have been dated to the time of the Champlain Sea and were crafted for the hunting of marine animals, such as small whales; intriguingly, the stone that they were crafted from is traceable to the coasts of Maine and New Brunswick. So early Native Americans in Burlington probably traded with other settlements just north, who traded with other settlements north of them, in series along the northeast waterways. There’s also ample evidence, including archeological finds and oral histories, that the Abenaki people later conducted smaller-scale agriculture in the area’s many floodplains, where there’s easy access to water and where flood deposits make for the fertile soils.

But waves of European settlement across Vermont brought enormous changes to the land. The early French explorers to the north traded the fur of species like beavers, fishers, and possibly even wolverines, reducing their numbers. When conflicts over land shifted the balance toward the English, the fur trade was supplanted by farming, marking another dramatic shift in relations to the land. Land began to be cleared for farming and habitation. Small subsistence farms shifted to larger commercial farms by the early to mid-19th century as Vermont became the epicenter of a global demand for Merino wool. Many more acres of forest were cleared, and wolves and catamounts were seen as threats to farm animals. Trapping and hunting were encouraged with bounties, which extirpated these and many other fur-bearing animals from the region. This opened enormous opportunities for smaller predators, like fox and coyote, while giving large prey species, like deer and moose, free range. What was left of the old forests in Burlington and elsewhere in Vermont all but disappeared, along with many animal species that required them, effectively finishing the work begun by the fur trade.

In this context, the birthplace of Burlington as a city is appropriately Winooski Falls. The first roads in the region were built to connect Rutland to the falls at Vergennes, Shelburne, and Winooski. These waterways powered mills that sawed timber and ground wheat, and allowed for the easy transport of goods in and out of the region. Later, as new markets for Vermont’s resources opened internationally, the first major street in the city, Pearl Street, was built to connect Winooski Falls to the docks along the lakefront. The waterfront grew into a busy commercial area focused on processing and transporting wood and other products to and from Vermont, the eastern US and Canada by water and rail. The iconic estates along Burlington’s southern hillsides were built not long after, some as a consequence of the wealth these new markets generated for a select few. Some wealth, like that of the Hickok’s, whose estate became the Five Sisters neighborhood, was from New York City or another urban areas – those families came to Burlington to buy land and semi-retire. The land associated with these large estates has since been subdivided and developed into the Five Sisters and Hill Section neighborhoods, as well as the Burlington Country Club and UVM’s Redstone Campus.

It can be difficult to parse the shape and influence of the landscape with this onset of intensive use. Nonetheless, some patterns still emerge: today, there are still productive farms on the flat, silty soils of the Intervale, on the clay-rich lake and sea bottom sediments south of town, and along the calcium-rich bands of exposed shale and dolomite. Unlike the rest of the state, stone walls don’t wend most Burlington woods; early farmers in the New North End cultivated nearly bottomless deltaic sands, where rocks were no obstacle. Today, this history is written in white pine, white birch, pin and black cherry, species that readily exploit disturbed soils, while cultivated species like black locust and red pine, still dot the woods here.

The modern era has brought further interventions at every levels of the Burlington landscape, and climate change promises to complicate this portrait with radically different variables. But in face of such monumental changes, the practice of parsing our landscapes retains weight and luster. Out of the richness and diversity found here–out of the full dimensions of time and space–it’s our hope that a larger, place-based perspective can help sustain the hope and resilience necessary to chart a way forward.

About the Authors:

Chris Ajello is a graduate student in UVM’s Field Naturalist Program. Alicia Daniel is a Field Naturalist for Burlington Parks, Recreation and Waterfront and Executive Director for the Vermont Master Naturalist Program. Thank you to Jane Dorney for consulting on the cultural geography portion of this story.

Thank you to Kate Kruesi for sharing her botanical expertise