Event Mapping

As I walk along the path, my students are scattered over the length of it – some on the trail, others in the brush, sitting, standing, sketching. They move at different paces, stopping when some sight or sound or texture catches their attention. One sits on the riverbank, capturing something on the other side of the water. Another kneels just off the path, detailing an insect. For many, this concept is new. There are no particular pieces that must be documented – scale and context and someone else’s idea of what is important do not factor in. Our lab session today has students hiking a short loop and documenting their experience through a process called event mapping.

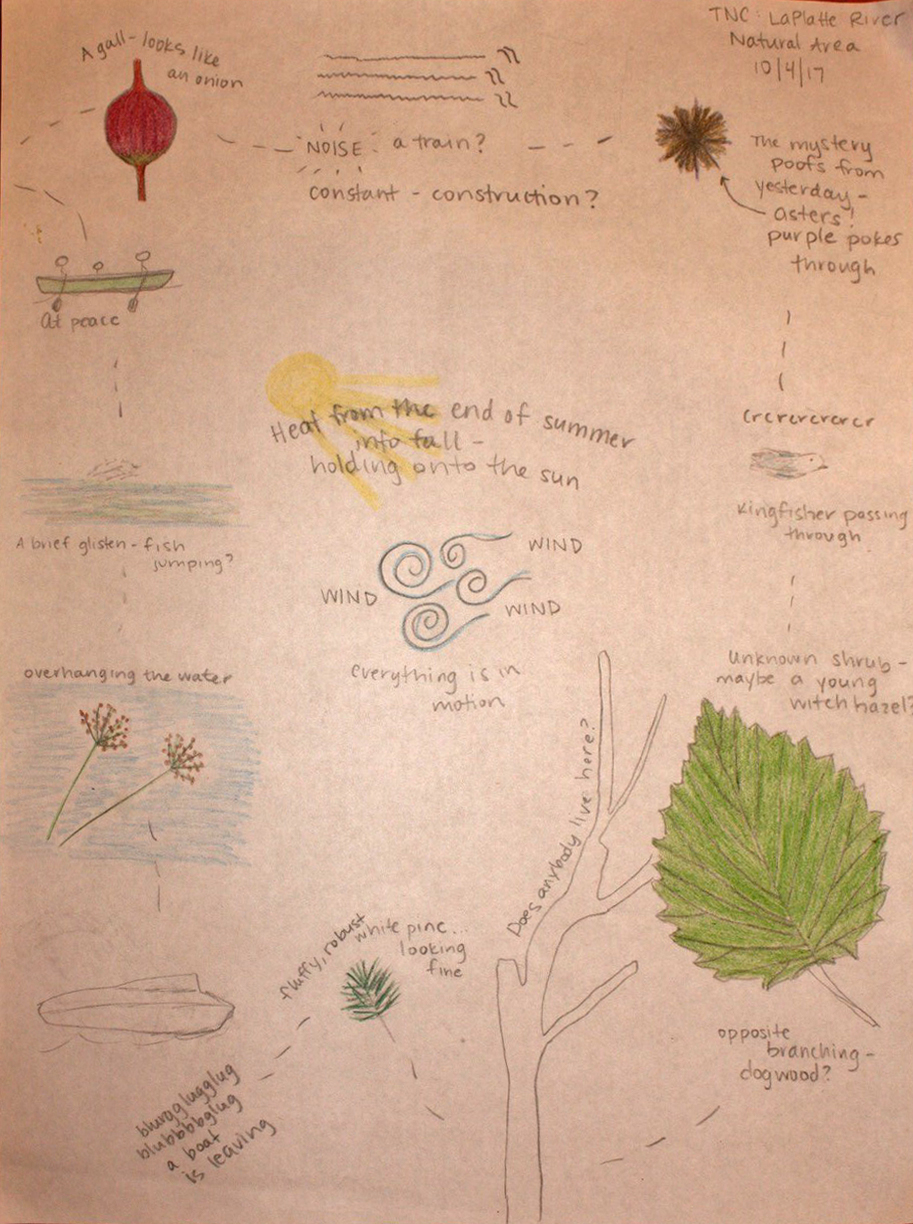

Event mapping, a term and practice developed by artist and writer Hannah Hinchman, is a way of noting an experience in nature through a combination of sketches and words that triggers sensory reminders of the day. Hinchman writes in her book, A Trail Through Leaves: The Journal as a Path to Place, the practice is “a simple mixing of words, images and symbols on a page, but it achieves things that drawing alone, or writing alone, seem to fall short of.” It isn’t a map to scale, but rather a lush representation of the sights, sounds, smells and textures that you encountered.

At the river with my University of Vermont class, I am making my own event map while the students create theirs. The first thing I have is on my paper is a fluffy tuft, drawn with streaks of pencil and purple colored pencil, with the words “Mystery plant – who is this?” swirling around it. Some dashed lines lead to the next thing that caught my eye – a canoe traveling down the river, sketched in red on my page with its own short note.

I was first introduced to event mapping as a graduate student in the Field Naturalist and Ecological Planning Program at UVM by Alicia Daniel, Burlington’s field naturalist and UVM professor. I fell in love immediately. Art as documentation was ideal to me, and having a creative and often colorful representation at the end of my field day was an added bonus. For me, the process feels more enticing than taking only written notes, and provides more information than a single sketch. Event mapping slows me down, and pulls me deep into the details of nature that I would otherwise miss. The process compels me to stop and hear or see things well enough that I can represent them on my page. Event maps to me feel at once both linear and untethered – they follow the chronological order of my explorations but allowing me to capture the whimsy and wonder.

I introduce event mapping to my students as one way for them to take notes and make observations. I hope that some students will grow to love the process, and at the very least they will have tried a new style of note-taking. I find that event mapping expands many students’ observational skills, and develops their ability as naturalists to pursue what they are curious about and focus their attention.

An hour later, the students trickle back to our starting point and lay out their maps in a circle. We move around them, exclaiming over the different things people have noticed – the unidentified bird of prey over the river, the brightly colored mushroom, the blankets of goldenrod. “Nobody sees a flower, really” writes the artist Georgia O’Keefe “it is so small it takes time – we haven’t time – and to see takes time”. In our world of technology and to-do lists, event mapping gives us the chance to really see the flower.

Each map is different, capturing the specific experience of the creator and the questions they hold. A grayscale, carefully shaded and detailed map sits next to one with loosely sketched pen lines, while a third is brightly colored. Individually and collectively, they form a shared memory of our past hour on the banks of the river. This, to me is the magic of event maps – to be drawn back out into nature, to drop in on a past series of observations and curiosities, to revisit the experiences of wonder.

Reference: Hinchman, Hannah. A Trail Through Leaves: The Journal as a Path to Place. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997.

Post Written by Laura Yayac