Ethan Allen Park Natural & Cultural History

The bluffs of Ethan Allen Park rise above Burlington as a 60-acre wildland showcasing some of the city’s greatest vistas and richest natural and cultural history. For a century, visitors to the park have enjoyed shaded promenades on carriage paths through old oaks and maples on hot summer days, family leisure at the playgrounds tucked in the monarch pines, and picnics in the gazebo at the grassy overlook called the “Pinnacle.” Blankets of spring wildflowers garnish the base of pastel cliffs, and thrushes sing in the dense forest understory all summer long. Erupting from the tallest canopy is the stately Ethan Allen Tower, an emblem of the New North End, which rewards visitors with unparalleled views of the city and sunsets over Lake Champlain.

From Rock to Tower

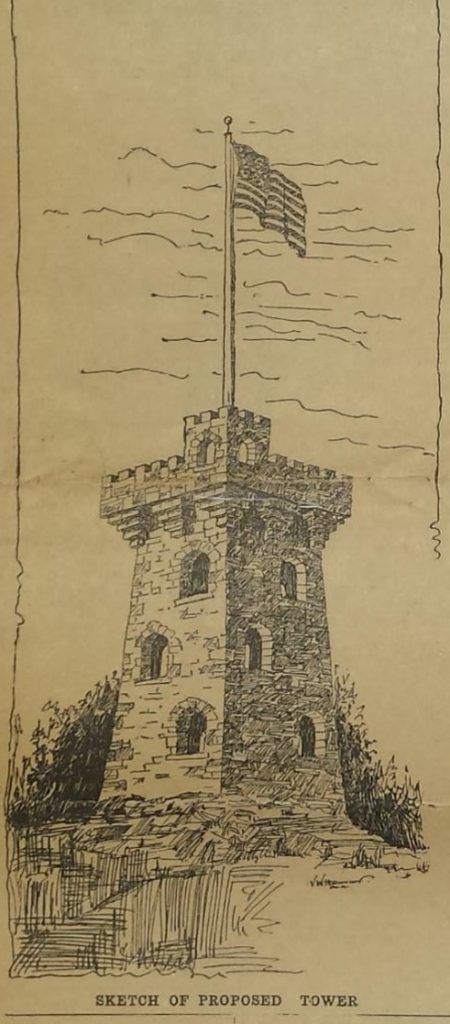

Though Ethan Allen Tower was officially erected to celebrate one of Vermont’s most recognized personalities, the 40-foot-tall monument is an equally appropriate memorial to the environment from which it was built. The tower designers reported that the structure was “intended to be built of stone which will be quarried near the spot, as there is an excellent opportunity to obtain it close by the proposed site. This will obviate all expense for material or for transportation. The stone is of the same character as what is known as Malletts Bay Marble, being very similar to that which has been quarried for the last year or two on the property of Mrs. A.B. Kingsland [1].” Explorers of the park may discover machine marks in the ledges and discarded boulders in the forest beneath the tower (visitors to the nearby Arms Forest, another Urban Wild, will even uncover Mrs. Kingsland’s quarry).

The strong, colorful stone across the entire park is a type of limestone, called dolostone, that has been strengthened and warped by the same tectonic pressures that caused the bluff to rise high above the surrounding city in the first place. Much of our topography is the product of a primeval tectonic collision in which Vermont was squeezed against the New York landmass over millions of years. The Green Mountains are the main site of the resulting buckling and uplift, but a grand view of the Champlain Valley reveals dozens of smaller buckled faults. Like a throw-rug pushed from one side, the landscape formed north-south running ripples, represented today by features like Mt. Philo, Snake Mountain, and Ethan Allen Park. The presence of an exposed rock outcrop, and the perfect building material conveniently on-site, are both of a single process.

Natural History Through the Ages

The park’s rich natural history deserves as much celebration as its tower. A 1904 Burlington Free Press article expressed as much:

“Another matter of interest to our people who are interested in botany is the extensive and unusual flora to be found there. A very large variety of trees and shrubs grow upon the property and also an extensive variety of the native wild flowers, including some rare orchids. There are also a number of very interesting ferns, including the rare walking fern [2].”

Today, naturalists recognize the park’s nutrient-rich dolostone as the source of this bountiful botany, as the soil it creates enables growth of a wide range of plants.

This nutrient-rich, dry landscape in the warm Champlain Valley nurtures a community of handsome trees like white oak and shagbark hickory uncommon to other parts of the state. Explorers will immediately notice the atypical size of these trees. Though some clearing was done in 1902 to open up 360-degree views at the park’s northern outcrop, the “Pinnacle,” the forest has been mostly undisturbed since. Even early visitors recognized the large trees as a main attraction.

Situated a stone’s throw from both the Arms Forest and the Winooski River floodplain, the park is as much a travel corridor for wildlife as for cyclists. This forested island surrounded by neighborhoods is a critical bridge for wildlife traveling across Burlington. Coyote, fisher, deer, and even moose move between the river corridor and upland habitats by way of this fragment of old woodland.

Because of its size and location in the context of Burlington’s network of open spaces, the park hosts a remarkable array of wildlife. Birdwatchers at the “Pinnacle” admire migratory warblers foraging in treetops. Coyote and fox droppings reveal the nocturnal users of the trail system. The old, naturally-managed forest produces a collection of large, rotting trees, providing cavities perfect for nesting barred owls, wood ducks, and woodpeckers.

White-tailed deer wander the edges of the park, bedding in the forest through the night and warm days, and venturing into private flower gardens at dawn and dusk. Though these deer receive varying degrees of appreciation by neighbors today, Burlington Parks & Recreation actually purchased and re-introduced deer into the park between 1912 and 1919, the herd managed and fed by a Parks employee [3].

From Tower to Community Park

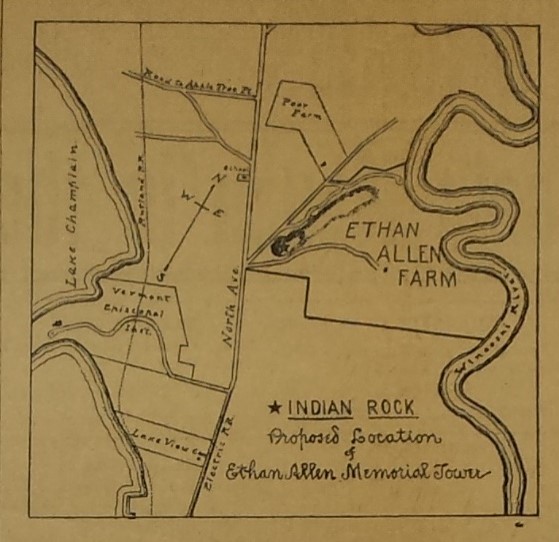

Though the Tower was built in 1905, humans have been attracted to its summits for millennia. The park’s southernmost outcrop has long been known as a strategic overlook used by the Abenaki to survey for Iroquois and Mohawk boats approaching from across Lake Champlain [4]. This fact has been fondly reiterated by white settlers for generations, who named the site “Indian Rock,” but there is little doubt of the outcrop’s strategic significance as Burlington’s best vantage point of the Lake Champlain basin. Perhaps because of these qualities, the outcrop was included in Ethan Allen’s own 300-acre farmstead extending all the way eastward to the banks of the Winooski River in 1787.

Charles Delaney, Abenaki leader, Burlington resident and former Chair of Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs speaks about the Abenaki use of Burlington’s high points.

Following Ethan Allen’s tenure, the farmstead and its outcrop changed hands unceremoniously for over a century until it was purchased by William J. Van Patten in 1902. Former Burlington mayor, philanthropist, and industry leader in Burlington’s South End, Van Patten recognized the bluff as an opportunity to provide the Burlington community with a world-class pleasure ground. Van Patten deeded 15 acres of the bluff to the Sons of the American Revolution (of which he was a presiding member), with the goal of erecting a tower to memorialize the property’s celebrated original tenant [5]. The SAR canvassed Burlingtonians to raise, in short order, the $2,450 needed to build the tower. They contracted Van Patten’s own business venture, the Champlain Manufacturing Company, to erect it [6]. Meanwhile, Van Patten informally consulted landscape architects and park planners across the country to inspire his design and installation of the recreational carriage roads he installed in anticipation of the tower’s completion.

In 1905, the tower was officially opened and dedicated in a lavish ceremony brimming with pomp and circumstance. Star-spangled bunting hung from buildings across Burlington, a marching band played in the city park, and a cavalry-led parade traversed the city, leading dozens of dignitary carriages to the entrance gates. President Theodore Roosevelt was invited to participate in the ceremonies, and thousands of visitors arrived by ferry and rail for the occasion [6].

Though Van Patten was the nearly-unilateral driver of the tower and initial 15-acre park, Burlington residents quickly developed pride and attachment to the new space. Residents found solace in this Progressive Era pleasure ground, a centerpiece of “Beautiful Burlington,” during this period of smoggy, unbridled industrialism. Burlington residents voted in 1907 to appropriate $10,000 to purchase the bluff’s remaining acreage from Van Patten: the first time in which the Burlington community collectively invested in land for a city park [7].

Residents enjoyed easy access to the park for decades. Madelyn Brewster recalled,

“… it was a summer day, the year possibly 1918, when we boarded an open trolley, traveled to the end of the line and Ethan Allen Park. After eating a picnic lunch, rides on the swings and slides, we would walk upward, through a narrow path that led to Ethan Allen Tower, and then another long trek to the top. I can still remember the panoramic view of Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains to the west, and Mt. Mansfield and Camel’s Hump to the east, etched against a blue sky [8].”

Below – Pre-1920 vintage postcards of Ethan Allen Park (click images to enlarge):

Courtesy of Special Collections, UVM Libraries.

The city’s attention eventually turned elsewhere and the tower fell into disrepair. With carriage roads overgrown, the tower vandalized, the park entrance gated to cars, and the trolley line long-extinct, the park became an inaccessible, myopic blank spot in the New North End for decades. Eventually, an infusion of interest by motivated Burlingtonians synergized with new city leaders who cherished open space began growing. In 1983, the tower was repaired, and Ethan Allen Park was reopened [9].

Today, the tower gates are unlocked each morning from Memorial Day to Indigenous People’s Day by passionate neighborhood volunteers. Along with their set of keys, these “Tower Keypers” carry a long legacy of community pride in one of Burlington’s most celebrated parks. Recreational users continue to seek out this preserved forestland for the same reasons as those visiting Ethan Allen Park over a century ago: to enjoy one of Burlington’s most beloved natural landscapes and unmatched overlooks.

Reference:

- “Memorial Tower to General Ethan Allen.” The Burlington Free Press. 29 November 1904. Reprinted by Sons of the American Revolution, Vermont Society. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- “Ethan Allen Farm” Burlington Weekly Free Press. 1 December, 1904. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86072143/1904-12-01/ed-1/seq-9/

- Leckie, Daniel. 2012. Burlington, Vermont Early 20th-century Postcard Views: Ethan Allen Park. University of Vermont. http://www.uvm.edu/~hp206/2012/leckie/webfinal/ethanallenpark.html

- Charles L. Delaney, Personal Communication. July 2016.

- Carlisle, L.B. Ethan Allen Park and The Van Patten Trails. Vermont History News. July/August 1983. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Vermont Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Exercises Attending the Dedication of a Memorial TowerEerected in Honor of General Ethan Allen Upon Indian Rock in Burlington, Vermont. Free Press Printing Co. 1906. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Burlington Should Own Ethan Allen Park. 1907. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- “Trip to the Tower Fondly Remembered” Burlington Free Press. 29 June 1986. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- “Saving the Tower” Burlington Free Press. 1983. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.