Crescent Woods

Tucked alongside Route 7’s busy corridor, this Urban Wild attests that rich stories and peaceful retreats hide in even the smallest of Burlington’s open spaces. Just beyond the sweet scent of black locust trees lining the street, a clandestine entrance through a brambly hedge welcomes explorers into a small forested oasis. The footpath follows fox and raccoon tracks to the edge of Englesby Brook, where the sound of traffic is replaced by tinkling water and wind sweeping through monarch pines above. The path continues over an enchanting stone bridge, through a garden of ostrich ferns, and between large maple, ash, and oak trees. Old, gnarly black willows sink their roots into the rich, wet soils at the edge of the brook. In the spring, rivulets form trickling waterfalls over the deep redstone quartzite formations exposed in the ravine edges.

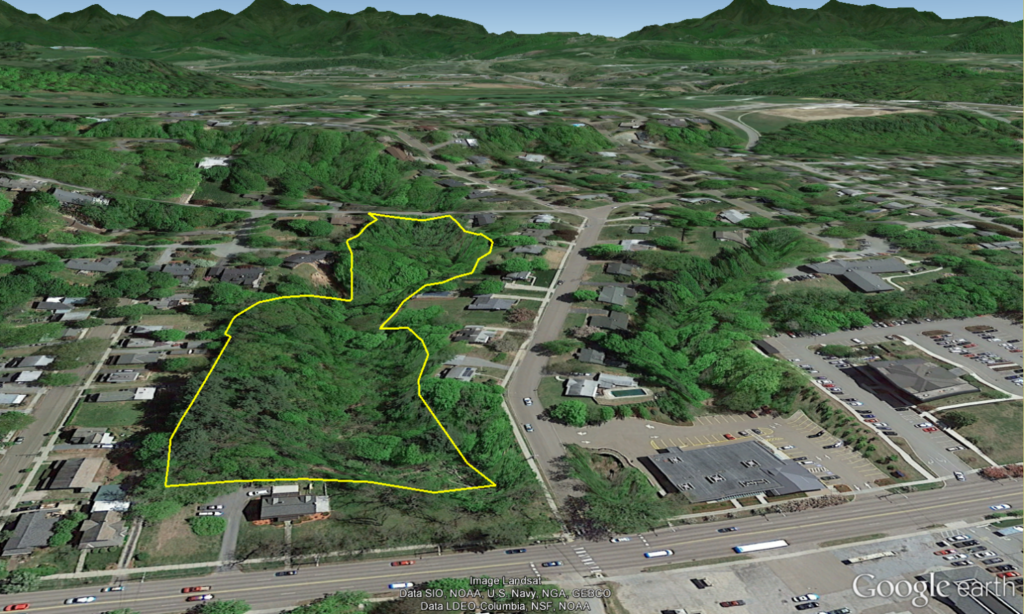

Crescent Woods is best understood as a remnant of its surroundings. Englesby Brook originates from tributary springs seeping from cracks in the redstone bedrock around the hillsides of the neighborhoods just beyond the park. The waters collect and flow through the park’s namesake crescent-shaped forested ravine connecting South Prospect Street to Shelburne Road. The brook once extended all the way to Oakledge Park, but has since been sunk under fill and culverts for most of its journey to the lake. Early-morning joggers and dog-walkers enjoy sauntering through this protected stretch of this historic ravine. Beloved by its neighbors, Crescent Woods has even been the site of Halloween haunted forests for youngsters in the vicinity.

A Mysterious Bridge

As visitors follow the trails, their first crossing of Englesby Brook takes them over a beautiful stone bridge of exquisite masonry. The careful mortar work, attractive river-smoothed stones, and its elegant design—complementing the natural landscape from which it emerges—is testament to the skill and artistry of architects of a different era. The inquiring eye notices the odd juxtaposition of this significant cultural landmark in a landscape that seems to have received much less attention. In reality, the stone bridge reveals the early plans for this ravine.

The bridge was ultimately the vision of a well-known New York City publisher, Henry Holt, who arrived in Burlington in 1890 [1,2]. Impressed by the beauty of the city and surrounding landscapes, Holt purchased large tracts of land over the next few decades extending from Shelburne Street east to Spear Street, north to Ledge Road and south to Swift Street [2,3]. On the highest point of land, Holt invited famous landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to survey the property and design a pleasure-ground estate commanding unmatched views of the Green and Adirondack Mountains for himself and guests [4]. The “Fairholt Estate” still exists today as the Burlington Country Club, and Holt’s house remains on the property.

After completing his estate, Holt turned his eye to his remaining lands west of South Prospect Street. Holt recognized a growing incongruity between Vermont’s picturesque landscapes and Burlington’s gridded, industrialized development trajectory at the turn of the 20th century. Manufacturing along the waterfront was progressing at fever pitch, fueled by coal-fired mills along the railroad tracks paralleling Pine Street. The city’s growing population funneled new residents either into overcrowded tenement housing, or into unimaginative, regimented residential blocks expanding from the city fringe. Inspired by a growing national movement to buck this development trend, Holt envisioned a new neighborhood that would be Burlington’s statement against industrial urbanization [5].

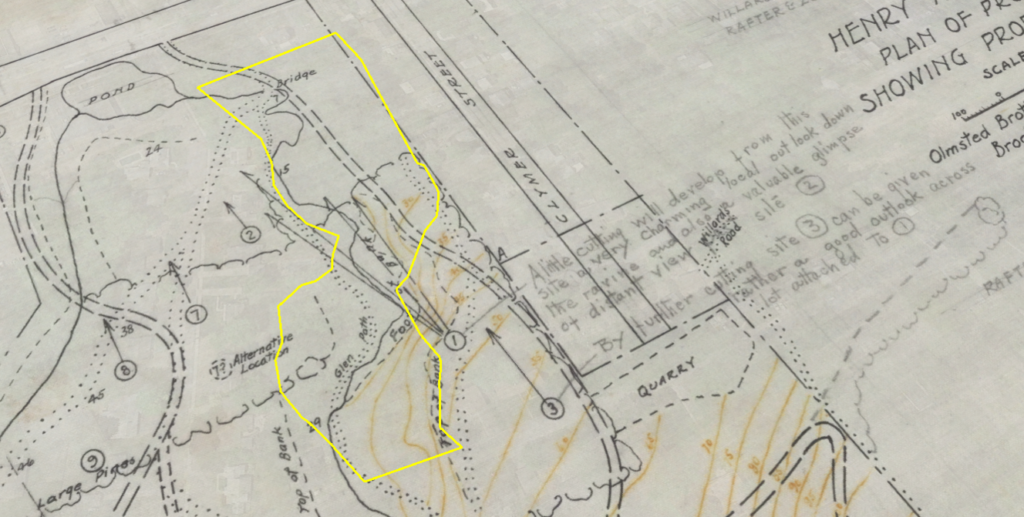

To accomplish this, Holt looked to Frederick L. Olmsted, Jr. and John Charles Olmsted, sons of the late Olmsted Sr., to continue their father’s design legacy. In 1914, the Olmsted brothers drafted their first plan of this “Prospect Park” neighborhood. The name was likely an homage to their father’s more-famous Brooklyn park, and chosen to create a sense of familiarity for the wealthy New York transplants that Holt intended to court as future residents [6, 7].

The neighborhood was perhaps Burlington’s first fusion of park design principles and residential community planning, blending nature and recreation into the living environment. Winding pedestrian paths and spacious house lots were designed to complement the fields, forests, and brooks that defined the preexisting landscape. Around today’s Crescent Woods, houses were sited to feature views down Englesby Ravine, with Lake Champlain as the backdrop. Recommendations for precision logging to improve the view shed were noted directly on the plans: “A little cutting will develop from this site a very charming local outlook down the ravine and also a valuable glimpse of distant views [6].”

At the edge of Shelburne Road, the Olmsted brothers proposed multiple layouts for “glen paths,” or natural wooded promenades, that ascended through today’s Crescent Woods, routed along the brook, over a bridge, up the ravine, and into to the neighborhood. The Olmsted Brothers emphasize preserving a stand of “cathedral pines” along the top bank of the ravine. Visitors today will recognize these giant trees towering over the park edges. Intriguingly, the proposed paths are drawn around a reservoir pond at the edge of Shelburne Road, created by damming Englesby Brook at its road culvert [6]. Whether the pond was a design element of the Olmsted Brothers or a preexisting feature remains unknown. Today, Prospect Parkway and the adjacent Kinney Drugs sit atop the former pond site.

The Prospect Park vision stalled out right at the advent of its implementation. Henry Holt died in 1926, shortly after the first subdivision was built along Hillcrest Road. The project continued to stagnate through the Great Depression and World War II. The Prospect Park Company, incorporated in 1902 by Holt and advisors to hold the land interest, continued to champion the neighborhood’s vision throughout this challenging period. The company references the Crescent Woods area of Englesby Ravine in an advertising pamphlet in 1937:

“Those nature lovers who for many years, both winter and summer, have enjoyed the glenway that runs from lower Prospect Street to Shelburne Road will readily visualize its future development, banked with wild-flower and rock gardens, ferneries, and shading groves, with a path following the brook course for the enjoyment of all residents of the Park [5].”

Despite decades of careful planning, the post-World War II housing boom welcomed speculators who purchased and subdivided the large vacant lots in Prospect Park. The neighborhood quickly filled with small, middle-class family homes typical of post-war developments [7]. Today, a discerning explorer may recognize the winding roads between Proctor Avenue and Ledge Road as a legacy of the Olmsted design. And visitors to Crescent Woods will immediately recognize the stone bridge as something dissonant with the neighborhood unfolding above the ravine’s banks: an emblem of a different era in Burlington’s relationship with open space.

Woodland wildflowers still grace the park’s ledges and springs, but Burlington’s cultural landscape has evolved since the peaceful glenway was first imagined. The park is a far cry from the intent of its original architects, though it serves the same purpose over a century later: a respite where residents may escape the frenetic pace of growth and progress while tuning-in to the sights, sounds, and stories of an open, natural space. As the Prospect Park Company explained, “The park is happily situated just where town and country meet. Its development contemplates that it shall always remain a part of both [5].”

Written and compiled by Sean Beckett and Samantha Ford in partnership with Burlington Geographic. Contact PLACE@uvm.edu with questions and inquiries related to this research.

Reference:

- “Prospect Park.” Burlington Free Press. 11 November 1902. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86072143/1902-11-13/ed-1/seq-5/

- “Real Estate Transaction.” Burlington Free Press.13 June 1890. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86072143/1890-06-13/ed-1/seq-5/

- “Boom for Burlington.” Burlington Free Press and Times. 12 June 1890. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Blow, David. Landmarks: Fairholt. Center City and South End News Vol 3 (9). 1978. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Holt, Henry. Prospect Park. Prospect Park Company, 1937. Pamphlet available at Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Project 01167. Olmsted Archives, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

- “A Vermont Tuxedo Park.” The New York Times. 12 November 1902.

- Andre, E.M. and M. O’Neil. Burlington Surveys of Prospect Park South and Strong Street. CLG Grant 05-02 Survey Report, 2006. https://www.burlingtonvt.gov/sites/default/files/PZ/Historic/sites-and-structures/ProspectParkSouth%20and%20StrongSt%20Summary.pdf