Mount Calvary Red Maple Wetland

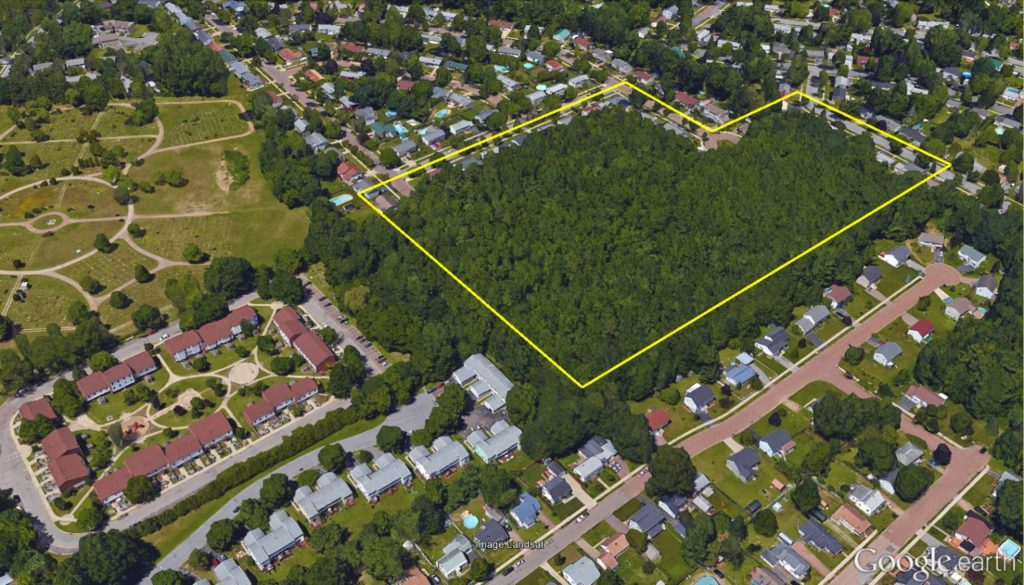

Squeezed on all sides by the core of Burlington’s post-World War II suburban neighborhoods, this is perhaps the last place one expects to find one of Vermont’s most bizarre landscapes. Visitors to the 12-acre Mount Calvary Red Maple Wetland (MCRMW) discover a landscape defying our expectations of what a forest—and a park—can be. That this open space exists at all is a tantalizing artifact of its odd natural history, fused with centuries of city planning evolution. An unusual geology enables dense flora more reminiscent of a jungle than a Burlington woodlot. Old boundary markers crisscrossing the parcel trace centuries of land use and development philosophies. And a surreptitious entrance though a break in an overgrown chain-link fence reveals the evolution of Burlington’s ethnic landscape.

Vermont’s Wettest, Driest Forest

Curious combinations of plants thrive in this woodland pocket. MCRMW is a far cry from the typical northern hardwood forests seen on Vermont postcards. Looking down, an explorer finds cinnamon and royal ferns: specimens that dazzle in red and orange autumn colors, but are generally relegated to the soggiest growing conditions of any Vermont fern. Looking up, the explorer notices pitch pines and black oaks: once-ubiquitous members of pre-settlement Chittenden County that prefer Vermont’s driest, sandiest growing conditions. The trails meander across dry forest floors, then pass over boardwalks spanning mucky water.

The naturalist looks for geological clues to explain the unusual juxtaposition of plants and soils. The adjacent New Mount Calvary Cemetery lies opposite the nearby chain-link fence. Flat, well-drained sandy sites enable deep, obedient graves, so the cemetery reveals that the region is situated on a dry sand plain. Dig a hole in the wet areas, however, and the explorer unearths a shovelful of fine silts and clays instead of sand. Eleven thousand years ago, the ancient Winooski River emptied into a much higher post-glacial Champlain Sea, depositing the enormous sandy delta composing much of Colchester, South Burlington, and Burlington’s North End. As rivers approach their deltas, main channels divide and feather into myriad rivulets and conduits coursing over the delta surface. Across MCRMW, imagine a near-stagnant, grimy side-channel of the Winooski flowing over this sand plain, moving so slowly that fine particles—those normally carried out into the lake—settled at the stream bottom.

The river has since receded into its modern-day margins, but evidence of those ancient backwaters are revealed today in the fine silts holding pockets of standing water across the site. A primeval outlet of the Winooski River thus yields a modern botanical mystery in this alternating dry and waterlogged forest.

Burlington Blueberries

World-famous 19th century landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead (designer of New York’s Central Park and our own Shelburne Farms) said of Burlington fruits, “I have eaten a better apple from an orchard at Burlington, Vermont than was ever grown in the south of England [1].” Burlington’s renowned fruit cultivation heritage is now obscured by New North End neighborhoods, but early 20th century residents recognized the New North End as Burlington’s pastoral end-of-the-line where children earned extra pennies picking berries and apples at the local small farms [2].

Mount Calvary Red Maple Wetland is the one place in the North End, perhaps the whole city, where children today can still go wild blueberry picking. Visitors will find the trailside lined with towering highbush blueberry shrubs reaching far overhead, the species perfectly suited to the unusually wet and sandy soils characterizing this site. And these bushes are likely the relics of this area’s berry farm history. A juicy pint of wild blueberries proves that treasure hides in the most unlikely of places.

Property Boundaries across International Borders

Unlike some of Burlington’s larger parks, MCRMW is not a product of a big philanthropic purchase, generous donation, nor generations of farming heritage. Instead, it is a lucky accident—the result of centuries of chopping, sub-dividing, and re-stitching of property boundaries in ways that allowed it to inadvertently dodge development. From British royalty to Somalian immigrants, MCRMW is a story of cultural evolution in Burlington.

Early Settlement: Burlington’s first property boundaries were drawn shortly after its 1763 chartering. In a single survey, millennia of dynamic Abenaki land practices were supplanted by rectilinear lines representing, for the first time, private property. For decades, Burlington’s original lots were traded like Monopoly tiles by speculating absentee proprietors. The land was traded from afar by lot numbers, with little knowledge of the features within.

Early town charters were issued under the authority of the British Crown. In English tradition, the King required that each town reserve certain lots as lease parcels. These rental lands were to be farmed, pastured, or logged, with rents earmarked to finance various services. The earliest rents supplemented the costs incurred by the King in establishing churches and schools. MCRMW sits in the corner of a 100-acre rental parcel designated as a School Lot, intended as a supplemental pasture or woodlot to be leased by neighbors [3, 4]. While these property laws are generally forgotten today, many small forests in New England towns exist because of their early history as long-term leases.

By the mid-19th century, Burlington had lost interest in its lease parcels, and many were sold outright. In 1843, Thomas and Amanda Northrop arrived from Connecticut to establish a humble family farm straddling North Avenue near its intersection with Plattsburgh Ave, including the entire School Lot [3]. Unlike some of the larger commercial farms that emerged towards the end of the century, the Northrops employed no tenants or laborers. They instead kept the work entirely in the family, except for the help of their two oxen and two horses. The fertile soils that attracted so many farmers to the Champlain Valley during this time eluded the Northrops, who eked out their 100 bushels of potatoes and “Indian corn” atop the poor, thirsty sand [5]. Today, old drainage ditches cutting through the wettest parts of MCRMW property reveal efforts of old owners, perhaps the Northrops, to redirect the wetland’s moisture to the parched fields nearby.

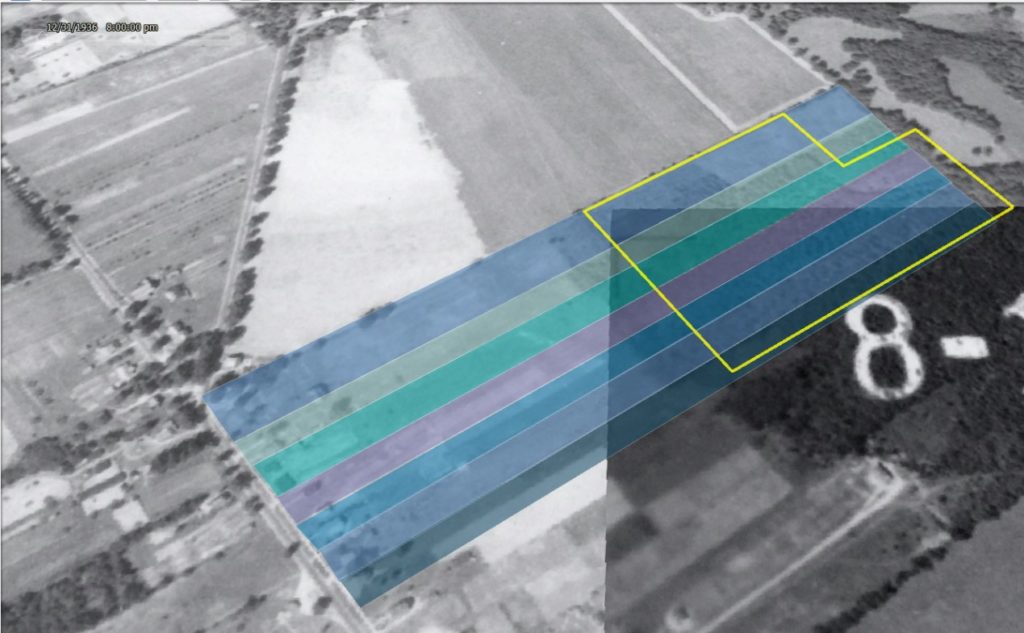

20th-century Development: By 1859, the Northrop’s son, John, had already put the farm up for sale, but it would take another eleven years before he found buyers for the last 60 acres, including today’s MCRMW [6, 7]. As commercial dairying expanded in the early 20th century, it exacerbated the divide in value between the sandy, landlocked farms on the North End, and the fertile intervale fields below. Meanwhile, a new housing market was emerging out of Burlington’s growing immigrant population. The New North End became an ideal site for new residences, and old farms were sold off as residential lots. The last 60 acres of Northrop farm were ultimately subdivided around 1910 into narrow, 100-foot-wide strips, each fronting North Avenue. The MCRMW area persisted as a mosquito-infested “back woods” of seven different residential properties—an un-farmable wetland set impractically far from the only road [8-13].

These property strips are easily seen in old aerial photos, which show abrupt changes in forest cover and density between each narrow parcel [14]. Though the forest has remained undeveloped as a whole, an explorer at MCRMW may notice these old property stripes by differences in the size of big oaks, old fence posts, and abrupt changes in the size of logged maple stumps around the property.

An International Forest

The neighbors and owners of these backyard strips of MCRMW land hailed from across the world. The 1910 owners of the pre-division parcel were a Jewish couple, immigrating from Russia and Poland, who ran a grocery store on First Street. They subdivided their lot into the seven strips and sold to a farmer from Holland, an Italian police officer, another policeman of a French mother and Canadian father, a firefighter from Germany, French-Canadian painters, and homegrown Vermont carpenters, teamsters, and railroad conductors [15-18].

In 1968, Burlington Housing Authority acquired these seven property strips and recombined them into one large parcel, developing the front half, along North Avenue, into the Franklin Square community apartments. The undesirable back half, MCRMW, was designated as conservation land to be managed by the City of Burlington [19]. Today, Franklin Square is a hub of Burlington’s New American immigrant community. As you walk through the neighborhood’s community garden plots to access the forest, you may be greeted by Somalians, Bantus, and Bhutanese. Not long ago, Bosnians, Serbs, and Herzegovinians might have been enjoying the park’s blueberries and fall foliage [20].

This 12-acre forest, against tough odds, remained intact through dozens of property transfers, divisions, and combinations over the last two hundred and fifty years. Its existence is the fusion of several coincidences: a near-arbitrary designation as a rental School Lot in the 18th century; a unique soil composition resulting in a rare, soggy natural history; economic relegation of the forest to a dissected and overlooked series of backyard mires. Today, MCRMW has been preserved, intentionally and unintentionally, as a landmark of Burlington’s natural, social, and ethnic tapestry. In a sense, MCRMW is a manifestation of Burlington’s evolution as a community.

Written and compiled by Sean Beckett and Samantha Ford in partnership with Burlington Geographic. Contact PLACE@uvm.edu with questions and inquiries related to this research.

Reference:

- Olmsted, F. L. Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England. Jos. H. Riley and Company. Columbus, Ohio. 1859.

- Charles Auer, Personal Communication, July 2016.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1843. Vol 16 p.244-245.

- Johnson, J. A Correct Map of Burlington, VT, from Actual Survey. 1810. Available at Special Collections, UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Eighth Census, Agriculture, Vermont. 1860.

- “Farm for Sale” Burlington Free Press.(Burlington, Vt.), 15 April 1859. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84023127/1859-04-15/ed-1/seq-4/

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1870. Vol 7. p.293

- Land Records, City of Burlington. Vol 54 p. 65.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. Vol 58 p. 481.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. Vol 58 p. 566.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. Vol 62 p. 224.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. Vol 65 p. 299.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. Vol 65 p. 379.

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. 1937. Aerial Orthophoto. Available at http://www.uvm.edu/place/burlingtongeographic/maps/index.php

- United States Census, 1910.

- United States Census, 1920.

- United States Census, 1930.

- United States Census, 1940.

- Land Records, City of Burlington, Vol. 188, p 165, 181, 257, 319.

- Craig Zumbrun, Executive Director, Burlington Housing Authority, Personal Communication, July 2016.