The Search for Sandplain Forests with the Master Naturalist Program

What do the woods around Starr Farm Park, the former Burlington College property, and the Arms Grant Forest all have in common?

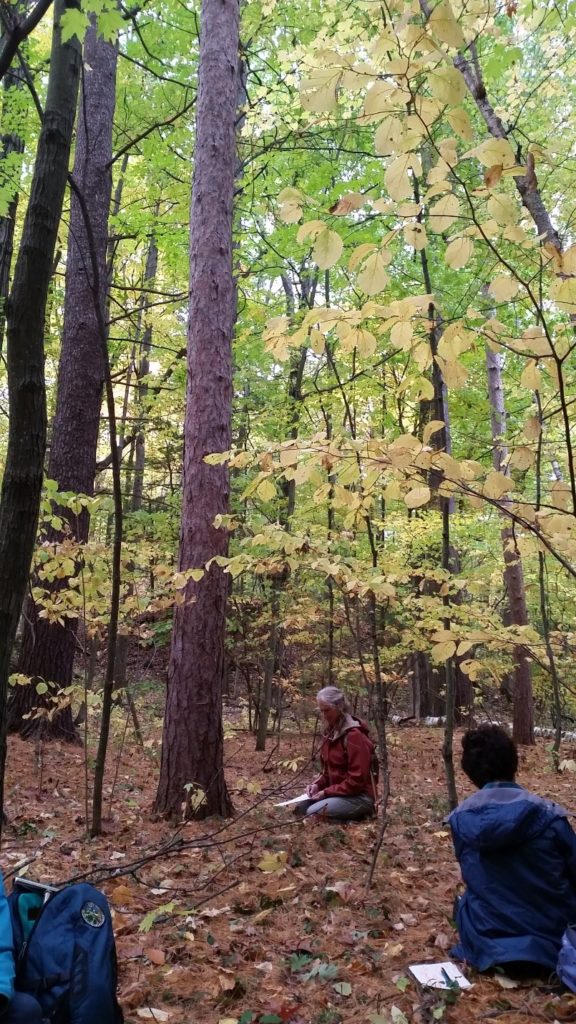

All three were visited last month by a group of Burlington Master Naturalists-in-training, who were on a City-wide search for “natural” forests in Burlington. Led by BPRW Field Naturalist Alicia Daniel, the group will be spending a total of four field days learning about the layers of Burlington’s landscape, from the bedrock to soils, plants and wildlife.

On this, the second day of their training, they pile out of cars at the end of Killarney Drive, notebooks in hand, looking to answer a question: What did Burlington’s forests look like before humans laid a network of sheep pasture, dairy farms, roads and eventually housing and commercial development atop them? Are there any natural fragments left or have some regenerated? And how can we possibly know what should be growing there, if it’s all been cleared away?

The key here lies in the soil; even with the forest totally cleared, the soil and physical environment dictate what plants and wildlife can occupy an area. Which is why our Master Naturalists file down to the shoreline of Lake Champlain and cast their gaze inland, where a recent landslide has revealed what soil lies beneath the flat expanse of the New North End: sand, sand and more sand, to a depth of some 30 or 40 feet. The sand is not uniformly mixed but rather lies in distinct layers or bedding planes, a sign that it was deposited by flowing water.

Alicia invites us to think back to 10,000 years ago, when Vermont was last covered by glaciers that spread like a tongue of ice from Canada to Long Island, NY. When these glaciers melted back, Burlington was covered first by a lake of fresh meltwater and then by an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that reached all the way down the Champlain Valley, called the Champlain Sea. The Champlain Sea was bigger than present-day Lake Champlain, its shoreline reaching all the way to the edge of the Burlington Airport (325 feet above sea level), with part of the current UVM campus forming an offshore island. With time the sea shrank down to our present-day lake, but it left a legacy of sand deposited wherever a river met its edge (when moving water meets still water, the large sand particles carried by the flow, lose their momentum and settle out, forming a delta). Our cars, parked above us on Killarney Drive, are sitting on top of one of these ancient deltas.

So what typically grows on delta sands in Vermont? A Pine-Oak-Heath Sandplain Forest (Vermont’s only sandplain natural community), which is a fire-adapted forest typified by an open canopy of pitch pine, red maple, and black oak. With this image in mind, we head up to the nearest patch of forest, at the edge of the Arms Grant Property (one of Burlington’s six “urban wilds”) to see what’s growing there. We find only one of our three target tree species, red maple, along with red oak, red pine, white pine, and hemlock. Despite being protected as an urban wilderness, years of fire suppression have led to a different make-up of trees and understory vegetation.

Now our search is on: Where can we find patches of this remnant native forest in Burlington? Next stop is the former Burlington College property, part of which is now City-owned. We find newly-planted oak trees and a couple of pitch pines, but the land is overrun by non-native species including the black locust trees that dominate the forest canopy. Maybe with a few more decades of management, we will get there.

At last our search comes to an end in an unexpected place: a sandy patch of woods between Starr Farm Park and the Starr Farm Nursing Center, part of the Flynn Estate. We find a beautiful early-stage Sandplain Forest with young pitch pine, oak and red maple, growing without human intervention.

At last our search comes to an end in an unexpected place: a sandy patch of woods between Starr Farm Park and the Starr Farm Nursing Center, part of the Flynn Estate. We find a beautiful early-stage Sandplain Forest with young pitch pine, oak and red maple, growing without human intervention.

All three of these Burlington forests hold the potential to grow back into Pine-Oak-Heath Sandplain Forest, which is recognized as one of the rarest natural community types in Vermont, but only one of them is currently deserving of that designation. We end our day faced with a final question to ponder: to what extent should we be acting as guardians of our present-day forests vs. gardeners seeking to return them to their native state? Once through their training, the Master Naturalists will continue working with the BPRW to guide the answer.

Written by: Sophie Mazowita

More info:

- http://vtdigger.org/2013/11/29/landscape-confidential-ancient-deltas-gift-glaciers/

- Wetland, Woodland Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont by Liz Thompson and Eric Sorensen