Arms Forest

The old forest landscape of the “Arms Grant” rewards visitors with rare natural communities and brims with clues of centuries of land use history. Visitors will find an extensive trail network lined with unusual plants, glimpses of deer and fox, and old farm roads shaded by rich canopies of centurion oaks. A hidden quarry even connects us to a Burlington that was once the national center of marble manufacturing. A rare gem in the necklace of Burlington’s open landscapes, this 30-acre park is located in the New North End’s largest area of contiguous undeveloped lands, nestled between Rock Point and the Intervale floodplain across North Avenue.

Forest Riches

A visitor to the Arms Forest may immediately notice a lush, diverse assemblage of wildflowers and vegetation unlike most Burlington forests. In the spring, before leaves emerge, explorers of the ledges and outcrops throughout the park enjoy wild ginger, red and white trillium, hepatica, meadow-rue, columbine, and other colorful wildflowers. The ubiquitous bedrock exposures are made of a nutrient-rich limestone called dolostone. Though exposed at this site, dolostone underlies much of the rest of Burlington beneath feet of nutrient-poor sediment. This unusual geology enables uncommon plants that require abundant calcium. In fact, these outcrops in the Arms Forest are home to rare plants, like yellow lady-slipper orchids, found nowhere else in Burlington.

Visitors may also note that the trees are uncommonly large for Burlington forests. The ledgy, thin-soiled nature of the property prevented its cultivation, allowing the forests to escape some of the agricultural clearing pressure experienced later in the area during the 20th century. The forest was largely used as evening pasture for livestock and a source of firewood for the farmstead’s stoves. Though none of the trees on the property pre-date 18th century European settlement, aerial photos from 1937 show that the majority of the forest today was present then. Older pines and oaks on the property have been aged at 100-120 years old.

This large, interior forest with immediate connectivity to adjacent tracts of undeveloped land provides excellent habitat for wide-ranging large mammals like deer, fox, coyote, fisher, and raccoon. Cavity-nesting birds like barred owls, screech-owls, and pileated woodpeckers live in the large, dead trees available in these old woods. In the spring, several small ephemeral pools trapped in the depressions of the shallow bedrock are perfect nurseries for forest amphibians like spotted salamanders.

Generations of Dairy Farming

Before the City acquired this parcel in 1962, this forest was part of a large, 400-acre 19th century farm. The Manwell Farm, so-called, stretched from the Episcopal Diocese property on the west, across North Avenue, and down to the Winooski River on the east. Philip V. and Esther S. Manwell purchased the property in 1868 from renowned local philanthropist Thaddeus Fletcher (whose daughter funded the establishment of the Mary Fletcher Hospital, now the UVM Medical Center) [1]

A brick farmhouse, constructed by Fletcher to house tenant farmers, stood on the land where Burlington High School’s parking lot is today [2]. It is unclear what other structures were on the property, but the Manwells cultivated a successful dairy farm over the next forty years. The fertile Intervale lowlands provided exceptional soil for growing silage corn and hay for the cows, while the forested uplands on the western side of the property allowed excellent pasturage and fuel wood. The farm’s location along North Avenue provided convenient access for buying, selling, and transporting goods.

After Phillip died in 1898, the farm began to decline. In 1903, his widow, Esther, married wealthy city plumbing inspector Allen B. Kingsland, and the pair moved to Cliff Street [3]. When Esther died in 1910, the farm did not have enough value to settle her debts. Rather than selling the land, relieving the debts and pocketing the extra cash, Allen kept the farm in operation. His intention was to revive the property in order to pay off his late wife’s debts, without any personal profit.

Through his oversight, the farm actually increased in value and became remarkably successful [4]. He brought in new bulls to “revive” the stock, horses were purchased to plow the old cornfields, and the milk tanks were fixed. The house and barns saw new coats of paint and roof repairs. In an effort to create more cash flow, Allen sold yards of high-quality Intervale soil to the neighbors and Lakeview Cemetery. The sale of the soil brought in enough capital to fund the revitalization projects.

Because of Allen’s decision to revive the farm, the land avoided the residential subdivision experienced throughout much of Burlington. For twelve years until his own death in 1921, Allen’s vision to keep the farm operable kept the agricultural legacy of the Manwells and Burlington’s North End intact [4].

Neither Esther nor Allen had direct heirs, so the farm passed to Esther’s adoptive nephew, Philip V. Sherman. Philip had lived with his aunt on the North Avenue farm, and later graduated from Norwich University with a degree in engineering. In a twist of fate, he was aboard the S.S. Tuscania in 1918 when a German U-boat destroyed it, killing 210 of the 2,000 men aboard, including Philip [5]. After a half-century of Manwell history on the farm, the property was purchased in 1921 to Burlington resident and UVM alum Willard Crane Arms [6].

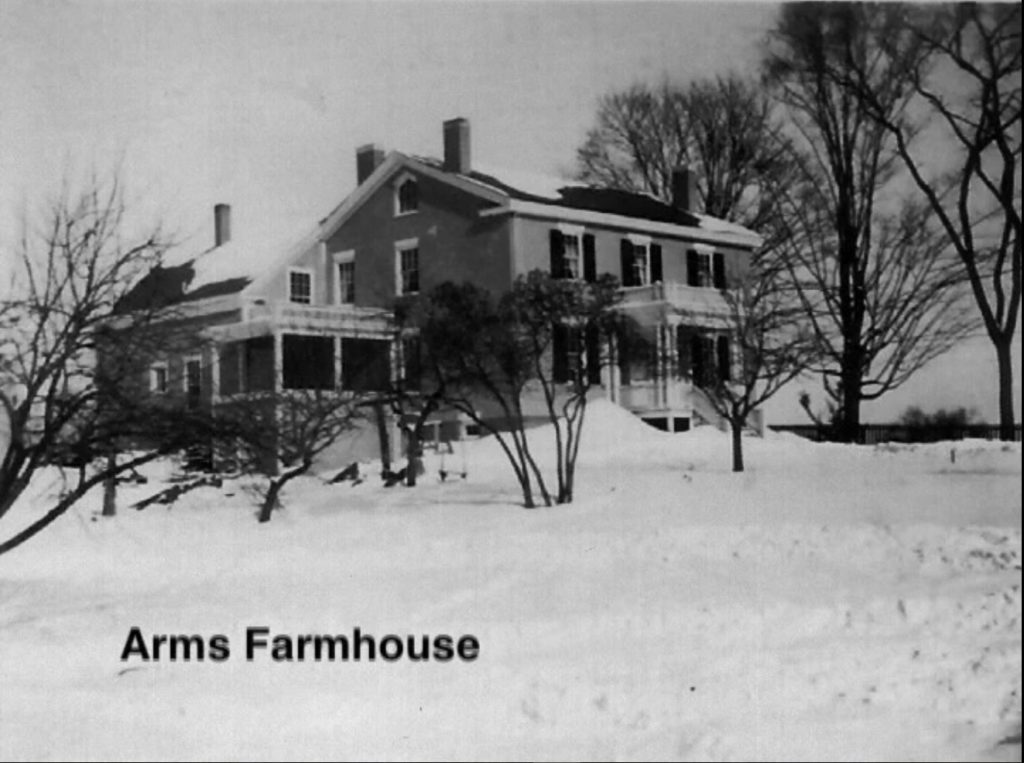

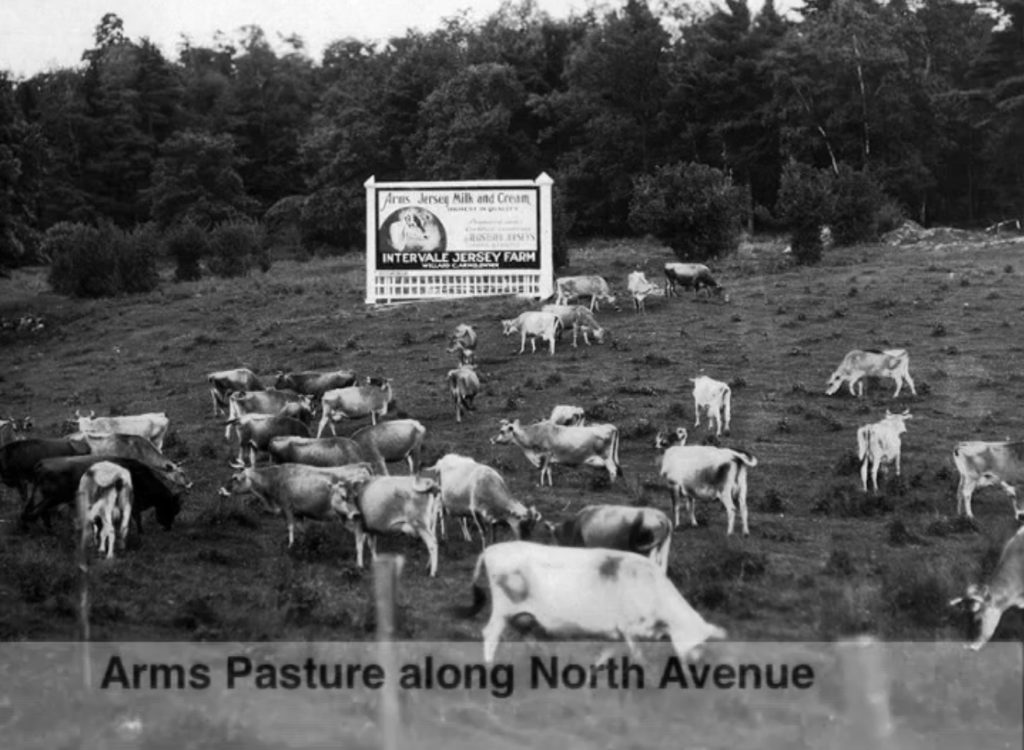

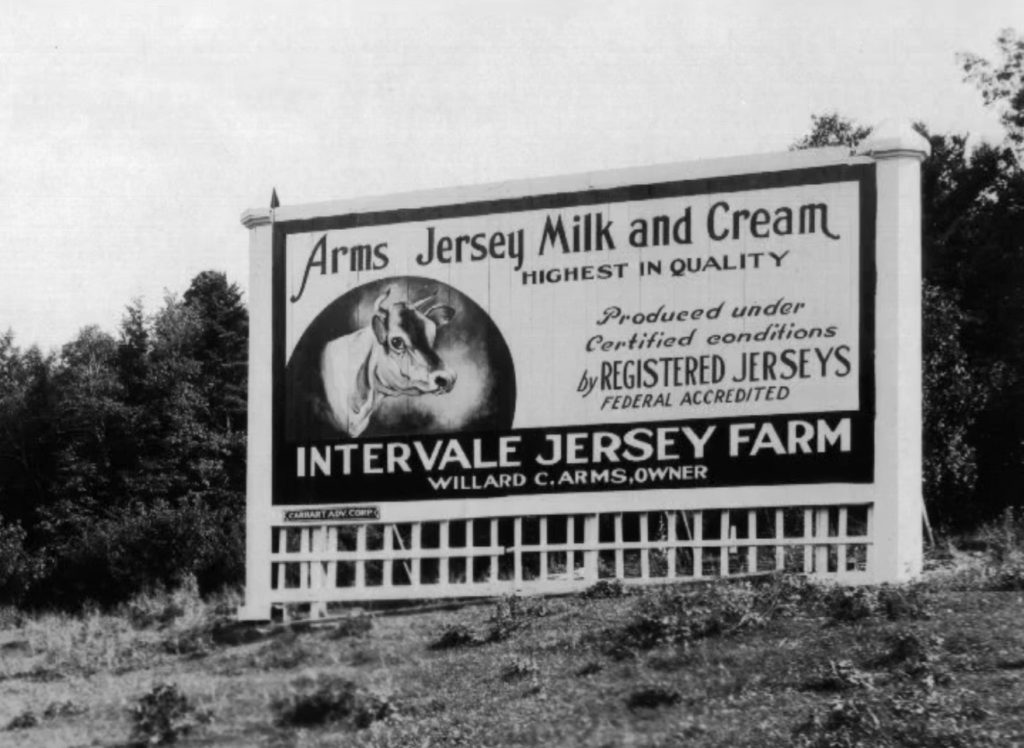

At $19,500 (about $279,000 today), the Manwell Farm was certainly a good deal for Willard [6], especially considering Allen’s dedicated management of the property in the years leading up to the sale. The following year, Willard married Florence Cummings (also a UVM alumna), and the newlyweds moved into the recently renovated farmhouse. They then turned their sights toward expanding the dairy operation into one of Burlington’s largest: the Intervale Jersey Farm. Each morning and evening, Willard drove his cattle across North Avenue moving the herd between the upland pastures for the night and the Intervale lowlands for the day depending on the season[7].

Listen to the Voice of David Arms, son of Willard and Florence Arms as he tells the story of the Arms family farm background. Courtesy of Kenneth Peck Studios.

Shortly after Florence and Willard’s establishment at their new farm, they leased the majority of the Episcopal Diocese lands at Rock Point as additional pasturage. In return, they would provide their Rock Point neighbors some friendly furnishings: three free quarts of milk per day to the bishop, wholesale milk prices to the Rock Point School for Girls, and plowing of the school’s gardens whenever necessary. Despite the formality of the lease, Willard occasionally received phone calls from the Bishop asking him to kindly remove cattle from the flower gardens [8].

In addition to producing raw milk and cream, the farm housed a processing and bottling plant. Each bottle rim was engraved with the phrase “a bottle of milk is a bottle of health.” On College Street, in the storefront west of today’s Leunig’s Bistro, locals enjoyed fresh ice cream at the Arms Dairy Bar long before Ben and Jerry would arrive downtown [9].

Willard and Florence were both graduates of the University of Vermont, and major supporters of environmental conservation for more than forty years. Willard served as the chairman of Champlain Valley Soil and Water Conservation Service. All who knew him referred to him as, “the salt of the earth.” Florence was an avid writer, she wrote frequent letters to local newspapers about the importance of maintaining open public lands and was a regular speaker at local groups advocating for “ecology.”

In 1962, the expanding population of Burlington necessitated a new high school, and the Arms property was chosen as the prime location. Historically at the “end of the line,” the Arms farm was now centered between the already densely populated Old North End and the next era of New North End suburbs. In a contentious process, the aging Willard and Florence agreed to sell their farm for the construction of the high school. The sale went through with the stipulation that the land behind the school remain undeveloped for recreation and education [10]. This was the first time a Burlington forest was protected for education.

Burlington’s First and Last Marble Quarry

Vermont was regarded in the late 19th century as the nation’s premier marble exporter. The long seams of limestone running north-south across the entire western side of the state were sufficiently compressed and metamorphosed to form marble deposits in some areas, particularly near Rutland and Proctor. Unfinished marble from these world-renowned quarries (examples of these blocks can be seen today along the Burlington Waterfront and the Colchester Causeway) were brought via rail to Burlington’s industrial waterfront, where several marble companies finished and polished the stone into tile, counters, and monuments. But for all the marble manufacturing that took place in Burlington, the city had no marble quarries.

At the southwestern corner of the Manwell Farm in 1887, a portion of outcrop was quarried to build Bishop Hopkins Hall at the nearby Rock Point School. This excavation revealed a dolostone formation beautiful enough to be considered marble by industry standards [11]. Previously, the only other attempt at harvesting local “marble” was in 1855 at Malletts Bay, at a quarry owned by George Perkins Marsh. This “Malletts Bay Marble” was highly durable and tough, but the hardness rendered the cost of extraction and processing much higher than the material was worth [12]. The Burlington Marble Company eagerly arrived at the Manwell Farm site in 1899, but testing revealed the stone to be similar to the Malletts Bay Marble. The possibility of a more successful local quarry that could furnish valuable resources could not be overlooked. The Company nevertheless signed a 20-year lease with Esther Manwell Kingsland for the old quarry. When Willard purchased the property in 1921, the deed was subject to the lease and quarry operations continued [13].

The Burlington Marble Company installed an access road directly to North Avenue and erected a tool house at the site, under the agreement that the quarry not interfere with livestock pasturage or farmstead operations. While there is little evidence of the whereabouts of the specialty “marble” extracted from this site, the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History received “two slabs of marble from the quarries of H.E. [sic] Gittins in Burlington, Vermont,” in 1916 when George W. Gittins was the director of the Burlington Marble Company [14]. The lease ended in 1925, and due to the high cost of processing combined with the departure of Burlington’s marble manufacturers, the quarry was permanently closed [15].

Today this hidden quarry collects lichen, moss, and curious inquiry from visitors. Leftover car-sized cubes of cut stone lay at the base of a small, exposed cliff. Though the property is crisscrossed by several miles of official and user-created trails, the old east-west running access road connecting the quarry site to North Avenue stands out, but is slowly being obscured by the surrounding forest.

Flowers and Footpaths

The outcrops around the Arms Forest showcase a curious conflict of modern property use. Rare and showy wildflowers blanket the park’s ledges each spring, some of which are the only examples of their species in the whole city, such as the spectacular yellow lady-slipper. Recognizing these rare plants as a key element in Burlington’s natural heritage, Burlington Parks, Recreation & Waterfront designated the area as an Urban Wild to protect these resources into the future.

Incidentally, the geology that is so perfectly suited for the yellow lady-slipper and its allies is also perfect for technical singletrack mountain biking. Avid cyclists seeking this terrain must otherwise drive at least half an hour to access similar “rock gardens” outside Burlington. The city’s Urban Wilds are managed to conserve sensitive natural and cultural resources, but this natural management approach over the years has resulted in community members constructing unofficial trail networks through the forest, causing significant erosion and trampling of the park’s most sensitive vegetation.

The Arms Forest was not designed as mountain bike park, yet the cycling community is one of the dominant and most passionate user groups of the property. While the current pattern of mountain biking is unsustainable, the cycling community is collectively one of the most prominent groups advocating for the long-term conservation of the park land and protected open space across Burlington.

The creation of a sustainable multi-use trail network within Arms Forest is one of Burlington’s major ongoing park planning conversations: How do Burlington residents value open space? What does responsible stewardship of these common grounds look like? How do we weigh conservation and recreation at the scale of a single flower, a single park, and the entire network of Burlington’s open spaces?

Forest Legacy

Today’s Arms Forest is used by a small number of passionate residents. The forest is popular for walking, running, dog walking, mountain biking, and is routinely used by Burlington High School and Rock Point School classes and athletic teams. While the quarry is an obvious human feature, the farming heritage of the Manwells and Arms touches the entire landscape. The size, age, and richness of the forest, conserved into the 21st century, is a testament to generations of successful farming, and the land use priorities of a single family and an entire city. Hopefully the next chapter in this park’s history will include the thoughtful management of a modern backyard wilderness.

Written and compiled by Sean Beckett and Samantha Ford in partnership with Burlington Geographic. Contact PLACE@uvm.edu with questions and inquiries related to this research.

Reference:

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1868.

- “A Landmark Passes.” Burlington Free Press. February 22, 1964. Available at UVM Bailey/Howe Library.

- Burlington City Directories, 1898-1903.

- “Esther Kingsland.” Probate Court Records, Chittenden County. 1910.

- “Vermont Office Among Missing.” Burlington Weekly Free Press. February 14, 1918. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86072143/1918-02-14/ed-1/seq-7/

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1922.

- Ann Arms, Personal Communication. July 2016.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1925.

- Ann Arms, Personal Communication. July 2016.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1962.

- “Hopkins Memorial Hall.” Burlington Free Press. October 14, 1887. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86072143/1887-10-14/ed-1/seq-2/

- Lowenthal, David. George Perkins Marsh, Prophet of Conservation. Seattle: U of Washington, 2000.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1909 & 1922.

- “Report of the National Museum.” Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. 1916. Pg. 142.

- Land Records, City of Burlington. 1925.